10 Apr Smart Shipping, the no brainer alternative fuel

The best energy is the energy we do not consume; how successful Smart Shipping can save money and time.

The maritime industry is overwhelmed with debate over the right alternative fuel to meet environmental goals. The selection criteria must take into account multiple parameters, like safety, emissions, cost, availability and maturity, if not mere feasibility.

However, the best energy is the energy that we do not consume. Therefore, Smart Shipping is the best alternative fuel. In fact, effective digitalisation of maritime operations increases safety, reduces emissions and optimises costs, and many advanced digital solutions are mature and easy to deploy.

What is at stake?

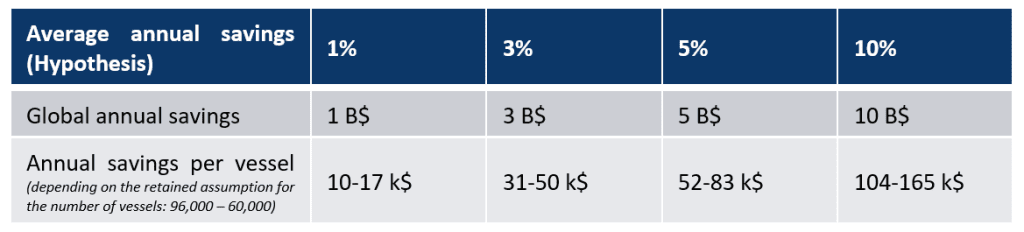

According to the IMO, international shipping consumed about 200 million metric tons of fuel in 2020. If we assume an average price of 500 USD/MT, the total annual cost of fuel is USD 100 billion globally. This represents about 608 million tons of CO2.

Regardless of the methods and tools used to save energy, the impact of such measures is significant:

Moreover, these savings estimates do not include the direct or indirect impact of current or future regulations (CII, FUEL EU, EU ETS, etc.). In addition, the majority of shipping professionals would agree that achieving a 5% to 10% saving is possible with simple operational measures assisted by technology.

In fact, in this HullPic 2023 conference article (page 151), Navigator Gas reports being able to cut consumption and emissions by 15% using Smart Shipping tools. Typical vessel performance optimisation features used are:

- Hull and Propeller monitoring

- Trim optimisation

- AUX and boiler optimisation

- Cargo cooling optimisation

- Targets monitoring

- Weather Routing

- Reporting automation

- Awareness and alerts.

Data quality is key

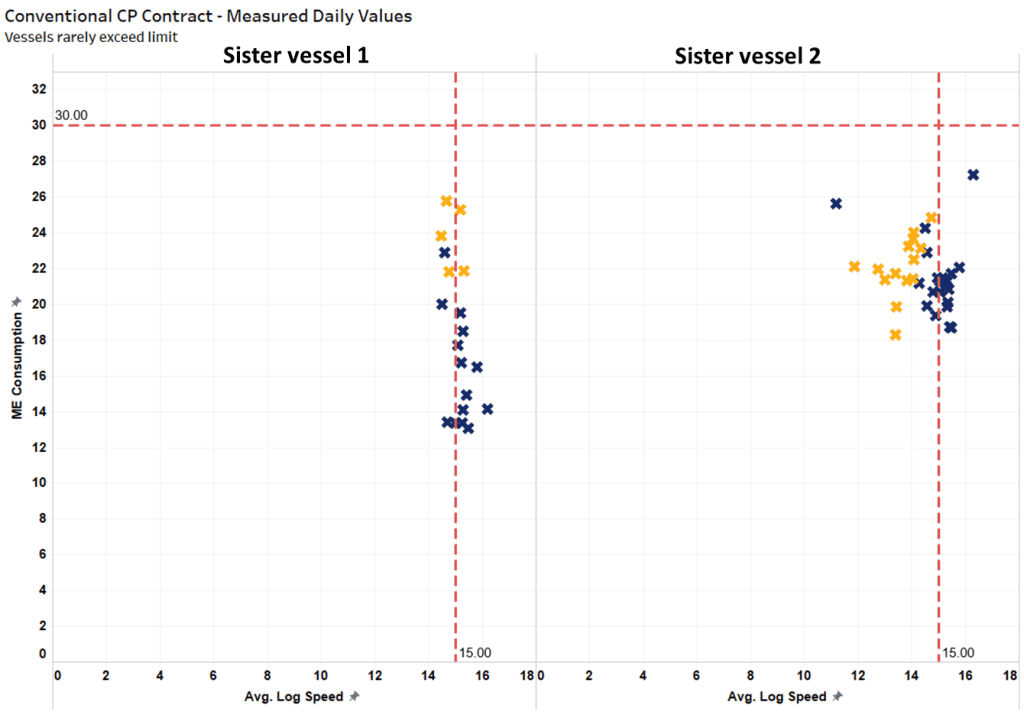

We often say that we cannot improve what we do not measure. This remains valid in cases of poor measurement quality. In the bellow chart, we see how sister vessels serving the same trade are reporting in a completely different manner.

Vessel 1 presents a plausible behavior. At the beginning of the docking cycle, the fuel consumption is low. At the end of the docking cycle, the consumption is high because of hull and propeller fouling. Regardless of the reasons behind poor reporting for vessel 2, it goes without saying that with poor reporting like this, there is little room for performance analysis and improvement.

Use case: Machinery optimisation

For many years, vessel performance optimisation potential has been hindered by the misalignment of interest between the charterer and the ship owner. Machinery optimisation is a very interesting use case, where both parties are incentivised to perform. In fact, if the fuel cost is supported by the charterer, in most cases, the cost of engine maintenance that depends on the running hours is supported by the ship owner.

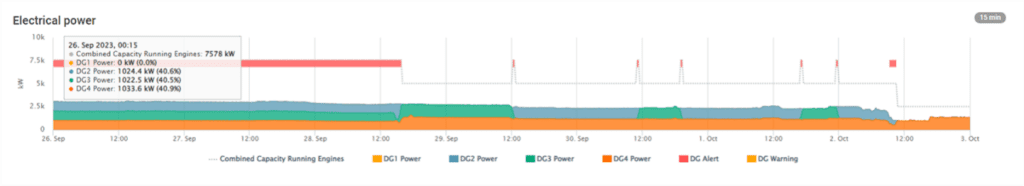

Here is a real example:

If we look at the period between 26/9/2023 and 28/9/2023, the vessel utilised more DGs than needed (3 instead of 2). After being alerted, the crew ceased using 3 DGs for the frame 29/9/2023 until 3/10/2023.

If we extrapolate for the year, this represents a saving of 54,750 USD in fuel cost and 8,760 running hours of the DGs. For that specific DG, the overhauling hours are 16,000, so the maintenance savings are around 70,000 USD per year.

This use case represents a yearly saving of around 124,000 USD per year. Furthermore, this does not take into account the impacts of regulations, like CII and EU ETS, on direct and indirect costs.

Use case: Voyage optimisation

Route-planning and optimisation involves juggling many constraints related to safety, operations and compliance. For ship captains, this is an essential and complex task that requires the aid of a decision-supporting tool to give them confidence and support execution.

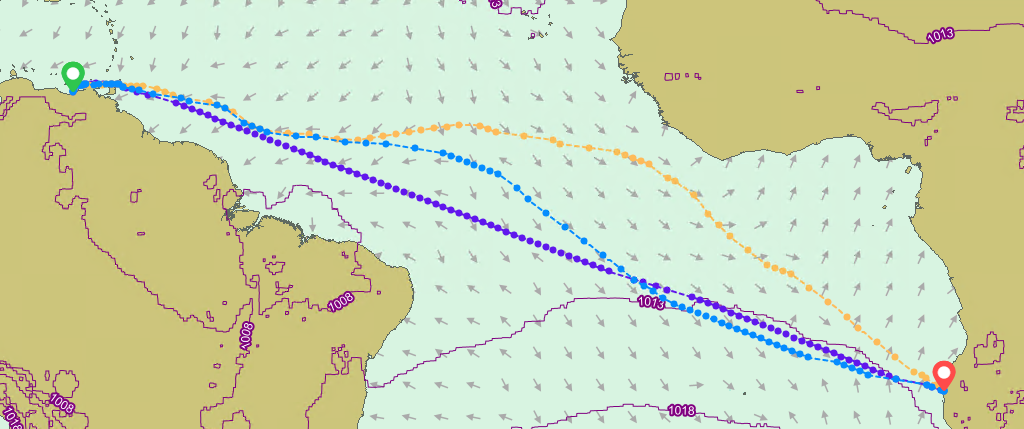

Depending on the optimisation criteria selected by the user, the routes can be very different. In the below example, we see three routes corresponding to three different criteria:

- Least fuel in orange

- Shortest distance in purple

- Lowest total cost in blue

In this example, the savings achieved in the “lowest cost” scenario in comparison to the “shortest distance” scenario is about 10%.

Barriers to effective vessel performance initiatives

When it comes to deploying digital solutions to help achieve the economic and environmental objectives of a shipping organisation, there are many challenges to overcome, such as:

- Misalignment of the stakeholders interests

- Lack of commitment or sponsorship within the organisation

- Overpromising from suppliers

- Unstructured approach to the project

- Lack of internal resources

- Poor risk management during the project definition, initiation and execution

- Lack of collaboration and transparency between internal and external parties.

It goes without saying that there is no single recipe to be applied uniformly to all projects. However, most of the time, vessel performance management initiatives are evaluated from a technical point of view. While technology is key, the methodology to deploy it is also critical.

We have seen many times how the deployment of vessel performance management projects successfully delivers expected results; and how, unfortunately, others have failed to do so. Very often, the reason resides in the absence of a methodology that builds confidence and trust in the vessel performance management project.

About Ascenz Marorka :

Ascenz Marorka, a GTT company, is a leading provider of digital solutions for Smart Ships in the maritime industry, offering one of the most comprehensive, innovative and reliable digital platforms for ship owners and charterers around the world.

Our mission is to deliver the most comprehensive, innovative and reliable smart shipping solution to ship owners and charterers globally. We offer a complete range of solutions, including sensors, modular suite of software and expert services. With over 20 years of experience, we’ve equipped vessels for over 160 customers worldwide. We are dedicated to innovation and collaborate closely with our customers to create a safer and more sustainable future.

Find the latest news on Ascenz Marorka :